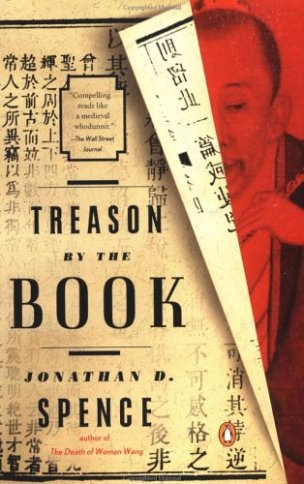

After my post last week about Jonathan Spence, I thought I would continue on the East Asian theme.

One of the best books about Modern China I’ve read in the past year has to be Liao Yiwu’s God is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived and Flourished in Communist China.

Don’t let the title fool you–it is not meant to imply that Liao believes God supports the “Red” Communist Government. Rather, since Red is the Color of Life in Chinese Culture, it comes from the assertion within the book, by a Christian convert, that God is Life.

The book allows many Chinese Christians to speak for themselves and explain why they find Christianity compelling.

Liao came to this subject in an interesting way. He was originally a musician and a poet. In the wake of Tienanmen Square in 1989 he became a dissident. Being outside of official recognition pushed him into contact with common people from all walks of life. Liao would interview them and interject his own reflections. This method was first evident in his book The Corpse Walker. (If you want to think about “dirty jobs”–how about picking up a corpse and “walking” it back to its village?) In his wanderings, Liao discovered that Christians were some of the few people who 1) seemed to have hope in dire situations and 2) showed real concern for the poor and outcast. The best example of the second impulse comes from a doctor. Although well-trained, he practices his medicine among the Miao people, healing their bodies and supporting the indigenous church.

For this project, Liao decided to focus on Christians in contemporary China. He largely allows the Christians he meets to speak for themselves, so there are long passages of interview transcripts. These “unfiltered” reflections speak powerfully to the experience of Christians in China over the past century.

Four moments encapsulated both the pathos and triumph that has to be part of the story. First, Liao and a friend visit an overgrown graveyard down a side road. It turns out this was part of a European missionary complex in the first half of the twentieth century. The missionaries had been expelled and the compound torn down, but a few memories remained, and churches in the area could still trace their roots to those endeavors. Second, Liao visited a Catholic monastery compound. The only remaining nuns were very old, but they were determined to keep it operating until their deaths and perhaps to see it revitalized with a few younger novices. Third, Liao visited with a Christian family that had suffered under the Cultural Revolution. Family members had suffered physical and psychological torture, and they had lost all of their possessions. Still, they maintained their Christian confession intact. Even that great suffering could not trump their beliefs. Finally, Liao visited a House Church pastor who was under house arrest. He and his family recounted their deprivations, as well as their on-going games of cat and mouse with the authorities. Altogether, these pointed to the weight of official persecution that had occurred, yet how remarkably resilient these Christians were.

In short, this is Chinese Christianity at the ground level. The result is profound.

In the last chapter, though, Liao interviews a young, urban male convert. He seems more interested in Christianity because it’s popular than because of any specific doctrines. This may point to a challenge in the coming years. As the Church expands, how does it continue to engender commitment among growing numbers of converts? On the other hand, continued pressure from authorities (whether directed by Beijing or not) could continue to keep the movement constantly alert.

In the global expansion of Christianity (highlighted a decade ago by Philip Jenkins), the growth in China has to be given a very prominent place. Since solid statistics are impossible to achieve, the exact numbers aren’t currently possible. However, the magnitude is definitely huge. Even more remarkable, this growth has occurred as an indigenous movement. Western Missionaries have been gone for sixty years, but the Church has exploded. Further, the development of the Church in China will continue to be important for World Christianity. To that end, Liao’s book might be read profitably next to David Aikman’s Jesus in Beijing.

Finally, let me say that I think this book would be great to teach. I can’t foresee an opportunity to teach it, but you can be sure that I’m looking for one.